Shokoku-ji is a Rinzai Zen compound consisting of 12 temples and the sodo, where the Roshi (zen master) and the monks, live and train. It’s situated in central Kyoto, near Doshisha University and the old Imperial Palace where the emperor lived when Kyoto was the capital of Japan.

When I arrived in Japan I lived in one of the temples, Chotoku-in, and in the first few months I would move into the monastery during the week long Sesshins ( intensive training). After the most rigorous sesshin, Rohatsu, during the first week of December, the Roshi ordered the monks, over their objections, to let me move into the sodo as a lay monk. There were only 6 monks in a monastery built for 90 and rather than see me as an extra pair of hands, they saw me as an American who would not be able to handle monastery life, who would get sick and need to be taken care of.

There are many detailed descriptions of typical Zen life that you can read if you are interested. However as you will read below, putting a 20-year-old North American in a 14th century monastery, new to the language, culture and zen way of life generated non typical incidents; some funny, some very meaningful.

1. Man San Creates Laughs and Brings in Extra Yen

Every monk is given a new sodo name. Either a shortened version of their name or a nickname. In my case it was an easy choice for the monks because they had a hard time pronouncing my last name. They decided to call me Man san.

One day during the winter, the head monk told me that the Roshi and all the monks except Moku san, were going to a nearby town to attend the funeral of a Zen priest. He said that Moku san and I were to watch over the monastery until they came back in the evening. Moku san was the least committed monk. He was the oldest son of a zen priest and needed to be in the monastery for 3 years so he could one day take over his father’s temple. In fact he once remarked, “Man san why are you here? I have to be here but you don’t.” So you can imagine that with the monks away Moku san planned on a relaxing day, and I didn’t mind giving my legs a rest from sitting in the lotus position.

We were sitting around having tea when a woman from the neighborhood came running into the monastery crying and screaming, and carrying either a sick or dead dog. Moku san recognized her as a parishioner who supported the monastery through donations. She told Moku san that her beloved dog had died and she wanted him buried immediately in the monastery, with a full Buddhist funeral service. Moku san reassured her that we could provide the burial and service in 10 minutes, and that we just needed time to change clothes . He told her that I was the youngest monk, an American, but that I knew the correct sutras and prayers. Then he pulled me aside and told me his plan. He was going to change into “samu” (work) clothes, get a shovel, and dig a grave for the dog. He wanted me to change into his finest monks robes and to deliver the funeral service.

My first thought was about the optics of me in his robes. Moku san was 5 feet and I was 5’ 9”. But I didn’t think that even mattered because I had no idea how to lead a Buddhist funeral. Moku san reassured me that I would be fine. He said the sutras that we chanted every morning were the same sutras that you chant at a funeral. So I put on Moku san’s robes while he dug a grave, and buried her dog. The three of us stood over the grave, Moku san sweaty and dirty, leaning on a shovel, the woman much calmer, almost serene, and I was dressed in beautiful black and gray robes that fit me like a short mini skirt. I used the notes that helped me in the mornings and I chanted loudly and confidently. After the service the woman was like a changed person, she was very grateful and almost gleeful, assured her dog was protected and going to a good place.

About an hour later she came back to the monastery and gave Moku san an envelope. In the evening, when the Roshi and monks returned, Moku san gave them a full description of the scene and the events. And then, almost sensing that they needed proof, Moku san revealed a large amount of money. The woman had told him she was giving an extra large donation because an American monk had presided over her dog’s funeral. Hearing the story and seeing the money, the monks had a very good laugh, and the Roshi even smiled.

A few weeks later, some family friends from the head monks’ home town made their annual visit to the monastery. The monks were very gracious and we interrupted our schedule to have tea and talk with them. This time no one mentioned that I was from the US. The next day at our morning tea ceremony, the head monk made some comments on the visit. The first part of what he said I understood, which was that his friends gave a larger than usual donation. But when another monk asked him why, he said something I didn’t understand, but it elicited laughs and looks in my direction. Gan san was the monk who was fairly proficient in English so after the ceremony I asked him why the donation was larger this year. He said that the head monks’ friends must have thought I was Japanese, and they felt it was so wonderful that the monastery now took in mentally disabled young men.

2. The Most Fun Day of the Year

Shokoku-ji was not on most lists of tourist sites. But our sister temples were probably the most famous and most visited temples in Japan. Kinkaku-ji (The Gold Pavilion), Ginkaku-ji (The Silver Pavilion) and Ryoan-ji, the Zen stone garden. These temples were situated at the edge of woods and mountains, on land that belonged to our group of temples.

Early one winter morning, the monks dressed in basic peasant clothes with tied cloth for caps, and they pulled out a flat board wooden wagon from the back of the monastery. They looked like extras hired to be villagers in a movie about 15th century Samurai. The head monk told me to get into work clothes because we were going to spend the entire day gathering wood for the year in the hills behind our sister temples. This was an important day because the monastery used wood fires for all our meals, and also to heat a big vat of water for our bathing (every 5 days).

So we lined up on both sides of the wagon, and as soon as we left the sodo entrance, we started running through the streets of Kyoto. It was a fascinating scene, the monks running in a rhythm, always looking straight ahead, but almost all the people we passed stopped to bow to the monks. It was the first time that I fully realized how much Zen monks were respected for their discipline and traditions.

When we got to the base of the mountain, we rested for a while. I asked Gan san why we ran and rested instead of just walked with the wagon. He said, “Because we are Zen monks”. The rest of the day was so much fun, especially with the contrast to spending hours each day doing zazen in the meditation hall. The whole day was gathering, not cutting down, any trees. We needed twigs, branches, and logs and we had the mountains to ourselves. There was a lot of talking, joking, tossing, and we enjoyed breaks for tea and rice.

We filled the wagon, ran back to the sodo to unload, and returned for several other loads. When we finished it was close to evening and I was exhausted but very happy. I took off my wet shirt even though it was the middle of winter, and steam was rising from my body. Drinking tea with the monks I felt l was part of a team and also part of a 600 year old tradition. It felt good to know we had wood for the year and it was all wood that was on the ground. Then the Roshi came into the monks quarters and thanked us all for our hard work on behalf of the monastery. A very good day.

3. Brooklyn Eating Habits Help Me Survive

In my career as a coach I often find myself explaining how a person’s greatest strength can also be a weakness if over used or used in the wrong situation. I guess the opposite can also be true. A bad habit can sometimes be a strength.

One bad habit exhibited by the men in my family was eating quickly. In fact I’m somewhat ashamed to admit that Freddy, Neil and I sometimes finished a plate of food before Zelda even sat down. Fortunately we usually ate two or three plates of food so I guess we still had family meals with her. In the sodo the meals consisted of an umeboshi (salted plum) and rice gruel for breakfast, miso soup with vegetables and rice for lunch, and warmed up leftovers from lunch for dinner. The rules during meals were, no talking, you had to eat everything on your plate, and if you ate quick enough and emptied your bowl you could get seconds.

So my Brooklyn family training came in handy for starters and I added the ability to shovel food in my mouth like someone training for the Coney Island hot dog eating contest. Even with my ability to get more food, and taking advantage of my twice a week Japanese lessons outside the monastery when I stopped for bowls of kitsune udon, I was dropping a lot of weight and came home at 138 pounds (when I was 19 I weighed 200 pounds)

The most important use of this skill came during the most intense sesshins, like Rohatsu. Rohatsu was designed to replicate the Buddha’s pledge to sit under the Bodhi tree and not leave until he was enlightened. The legend is that he meditated for a week and on the morning of the eighth day when he saw the morning star he experienced enlightenment.

So during Rohatsu we meditated day and night for a week, barely sleeping. With dinner at 3:30 pm around midnight I would be dealing with a mix of pain from the sitting in the middle of the winter with no heat, tiredness and intense hunger, as sitting in pain used up a lot of energy. Then at midnight I heard the most beautiful sounds of the entire year. Two monks running along the stone pathway, their geta (wooden shoes) clacking, carrying trays with bowls of steaming udon. Not only did each monk get a bowl placed on the ledge in front of where they were doing zazen, but if you managed to slurp down the entire bowl of hot udon you could get a second one. But you didn’t have much time. To me at the time it felt like the only way I was going to survive Rohatsu was to swallow two bowls of udon, so I didn’t care how hot it was.

After the monks left with the bowls and ran back to the kitchen, I got back into the lotus position but I gave up trying to mediate. For the next hour, each night, I just sat there and felt the pleasure of the hot udon warming my body and making its way to my stomach.

4. Cultural and Linguistic Misunderstandings

As you can infer by hearing about our eating habits, burps and belches were often heard in my family and in the general neighborhood. In the rare instance when someone actually said “excuse me” after an occurrence, many times a kid or an adult would say something like this: “If we were in China or Japan you wouldn’t have to apologize for belching, over there they consider it a compliment after a meal.” Silly me, I never questioned this cultural wisdom, and when I was in the monastery shoveling food from my bowl to my mouth every meal, I regularly belched after the meal. This went on for a couple of weeks and one day Gan san pulled me aside. He pointed out how much I was belching and I told him I thought it was considered a compliment. He corrected me and told me it actually was considered disrespectful. That’s what I got for taking cultural advice from guys who spent their whole lives in Brooklyn.

In 1964, in order for a male US citizen to get a 1 year visa to live in Japan you needed two things: a deferment from the US Army because I was draft age, and a Japanese sponsor for the visa. So after Cornell I took an Army physical, which I passed and the Army agreed to defer my enlistment for a year. This was before the Gulf of Tonkin incident, after which President Johnson drafted 550,000 men, otherwise I would have never gotten the deferment. Regarding a sponsor, while I was at Cornell I wrote to people whose books or chapters on Zen I had been reading. One of them, Sohaku Ogata, the priest in charge of Chotoku-in, agreed to be my sponsor and let me live in his temple. Ogata san was one of the few Zen priests at the time that was fairly fluent in English. Ogata san was an upbeat, optimistic person but when I was about to enter the sodo for Rohatsu he became noticeably nervous about the rigors I was about to face. He actually seemed convinced I was going to suffer some type of injury or illness.

Amazingly when the 8th morning of Rohatsu came I was still “standing” and walked wearily the 300 yards back to Chotoku-in. Ogata san was waiting for me and anxiously asked about my health. Because during Rohatsu almost everything except zazen, sanzen, and eating was suspended, we didn’t even have our once in 5 days bath. As a result I developed a rash on my thigh. So my answer to Ogata san was, “ I’m doing OK, I only have a rash” and I pointed to my thigh. He immediately responded, “We have to take you right to the hospital.” I was looking forward to a bath and sleep and said, “It’s only a rash” but he was determined, so off we went. It turns out that although Ogata-san’s English was pretty good he didn’t know the word “rash”. And he didn’t tell me that he didn’t know that word. I guess since he was convinced I would be injured when I pointed to my thigh it confirmed his fears. We get to the hospital and he talked with a young female nurse. She took me into a private room and indicated I should take off all my clothes.

So I went from a week of dedicating myself to Buddha’s path to enlightenment to an hour later getting naked in front of a pretty young woman. She looked at my thigh and said, “Hifu (skin) byoki (illness)”. That’s how I learned the Japanese word for rash. After I dressed she gave me some ointment and told Ogata san, hifu byoki. We got a taxi back to Chotoku-in and rode silently.

Looking back I probably was the first monk in the 600-year history of the monastery to end Rohatsu in the way I did.

5. Fear of Missing Out (on Zen Wisdom)

About a week after Rohatsu, the Roshi over-ruled the concerns of the monks and gave me permission to move into the Sodo. I had only been there a week when Gan san informed me that there was going to be a special ceremony on the night of December 23rd. He said this was the one night of the year the monks were allowed to drink alcohol in the monastery and that after the ceremony the drinking would start.

One thing about monastery life I should point out is that during the entire year the monks and the Roshi rarely talked about Zen or Buddhism on a conceptual level. There were also no books or reading. They told me how to clean, sweep, weed, sit, walk and what to chant but didn’t provide much other guidance. In fact once during sanzen (one on one meetings with the Roshi), he said, “ I would like to help you but you have to do things for yourself.” So on December 23rd after dark, the ceremony started and it seemed to be very spiritual and special. Everyone wore their best robes, there were many candles, bells, beads, statues of Buddha, chanting, and the Roshi walked in slowly and ascended to a high chair in the middle of the room. When he began speaking all of us prostrated ourselves on the floor and stayed there with our foreheads on the back of our hands.

The Roshi proceeded to give a lecture. As I mentioned this was so rare that I was sure he was sharing essential Zen wisdom and I was missing most of it due to my limited Japanese.

I made up my mind to get to Gan san as soon as the ceremony was over and before he started drinking. After the Roshi slowly left the room I dashed over to him and asked him to tell me what the Roshi had said. Gan san smiled. “The Roshi said that he knew some of us were going to get drunk tonight, and he asked us to be very careful so that we didn’t burn the monastery down. If we did he would have to kill himself.”

6. Sanzen Experiences

There are two main schools of Japanese Zen Buddhism, Soto Zen and Rinzai Zen.

In Rinzai Zen the Roshi assigns students a Koan or Mondo (problem) to solve through intense meditation. It is believed this helps create even more focus and intensity for the zen student. Heightening the urgency is the practice of sanzen, where on a regular basis the student meets with the Roshi alone and has to provide an answer to his assigned Koan. Some of the most famous Koans for beginners are: What is The Sound of One Hand, What was your original face before you were born, and What is the meaning of Joshu’s Mu (nothingness)? During sesshin weeks monks sometimes went to Sanzen two or three times a day.

Here is what the process looked like. We would be doing zazen in the meditation hall and when it was your turn the Jikijitsu san (monk with a large stick who monitored zazen making sure monks didn’t sleep or slack off) would tap you and you went to sanzen. The final part of the walk was along the roka (wooden walkway) leading up to the Roshi’s sanzen room. Outside the room you bowed, then prostrated yourself, and with head on the ground, raised your hands above your head (raihai) to respect the Roshi and the process. Then you took your place, facing him, about 3 feet away. You stated your Koan and then your answer. The Roshi then did a variety of things. Sometimes he scolded, encouraged, smiled, shook his head or just rang his bell indicating sanzen was over. The monk had to bow in front of him, head on the floor one more time before he left. Sometimes at that point the Roshi would whack you with the small stick he always held in his hands. He only weighed 95 pounds and the whack didn’t hurt much and I never knew if it was a good sign or a bad sign when I got hit.

Here are three sanzen experiences that stand out for me.

1. Over before it began- One time I hadn’t been trying hard in zazen when I went to see the Roshi. The roka leading to his room was old and if you weren’t centered and calm, walking on it could be noisy, especially on a quiet night in the sodo. That night as I was walking to sanzen I heard the Roshi’s bell before I even got to his room. He could tell from the noise that I was not centered and he didn’t even want to hear my answer.

2. Tripping up- The monks had robes but since I was a lay monk I simulated their dress by wearing a hakama, which looked like a long skirt. One sanzen visit, as I was making my first prostration at the entrance to the room, I stepped on the front of my hakama and fell forward on my face. The Roshi looked at me, smiled and rang the bell.

3. Nothing to lose- During the year I was at the monastery I went to sanzen over a hundred times. I would focus as hard as I could during zazen and hope that some answer would emerge. One time the pressure to come up with an answer and the frustration of always being wrong got to me. I made up my mind that when I got to sanzen and was positioned in front of the Roshi I was just going to scream in his face as loud as I could. If you ever meet my brother Neil, he will confirm that I had one of the loudest yells in our schoolyard sporting events. So I did all my bows and prostrations correctly, sat face to face with the Roshi, stated my Koan and without any warning, vented all my effort and frustration into a violent scream.

What happened next was unnerving. Nothing. He didn’t flinch, blink or change in any way. After about 15 seconds, he rang his bell and I left sanzen. I remember walking back to the meditation hall, feeling very strange. Even now 55 years later I can’t exactly describe the feeling I had. It was just an unsettling experience to scream like that without warning, so close to someone’s face, in a totally still monastery, and get no reaction.

7. Zazen

Zazen was a mix of learning how to concentrate and learning how to suffer. As the year went on my ability to quickly focus and center increased and my ankles, legs and back became more used to sitting in the lotus or half lotus position. As a result there were many more instances when zazen became a time of deep tranquility. A place where it seemed like all I needed in the world was to be able to sit and breathe slowly.

Abe san once gave me a famous waka poem by Nishida Kitaro, who was Hisamatsu’s teacher, that comes the closest to describing the feeling:

The bottom of my soul is so deep

Neither joy nor the waves of sorrow can touch it

8. Bad Job or Good Job?

The sodo had no hot water, toilets or sewer system. It did have two large iron vats. One vat in the bath house was situated over a pit. Once every five days we would fill it with water, and an experienced monk would start a fire in the pit to heat the water. The vat could hold 3 or 4 monks and the trick was to get in when the water was warm enough but get out before the bottom of the vat got too hot. On days when we did a lot of sweaty or dirty work we got to go to the bathhouse again. The other vat, about the same size, was buried in the ground in our outhouse. It was covered with boards, with the necessary openings for all of us to deposit our urine and excrement. When the vat became full it was the role of the youngest monk to empty the vat and recycle the contents.

When I got to the sodo, Moku san (23 years old) was the youngest monk and this was his job. After I acclimated to the sodo routine the task was passed along to me because I was now the youngest monk. They gave me a six-foot staff and two wooden buckets that attached to the ends of the staff. I had a scoop and filled the buckets, hoisted them on my shoulder and walked slowly about 300 yards to our fields where we grew our vegetables. At the gardens, I detached the buckets and carefully poured our waste into the rows to serve as fertilizer. Then I repeated my trip and it usually took me several hours to completely empty the vat.

If you had approached me during my senior year at Cornell and told me this is what I would be doing in 6 months, you can probably predict my reaction. It turned out that not only did I like this job, I looked forward to the days when I got to do it. First, it was really an extension of paying attention and mindfulness, except in this case it wasn’t hard for me to focus on what I was doing to make sure I didn’t spill the contents. Second, I enjoyed the break from pain, and walking in the sun felt delicious. Third, this felt like freedom. Most of the sodo day had a set routine but now I was free of supervision and on my own. Fourth, like gathering wood on the ground for our fires, I felt good about recycling everything and growing our own vegetables.

And I guess the last benefit was it got Moku san to stop pissing in the bushes next to the outhouse. When I first got there I saw Moku san repeatedly pee in those bushes. One day I asked him why because the outhouse was only five steps away. He told me that he was trying to delay the vat filling up because he was the one who had to empty it.

9. A Brush with Death as the Roshi’s Attendant

On the occasions when the Roshi made a trip, one of the more experienced monks would go with him as his attendant. This role required someone who could totally stay focused on the Roshi, and pick up on his signals.

A few weeks before my visa was about to end and I was set to return to the US, the Roshi was due for his annual trip to his hometown, Kyushu, in the south of Japan.

He had friends or some remaining family members there. He decided to take me as his attendant. So with advice from the head monk who had fulfilled this role, we headed out the sodo entrance, me walking three paces behind the Roshi. We took a train to Kyushu, sitting across from each other but staying silent. When we got to his friend’s house and sat down for a meal he became more animated. At one point the family served me a dish that I had a hard time swallowing, and when I hesitated eating it the Roshi shot me a glance like “don’t even think about it” so I ate everything on my plate.

The next day they took us down to the sea and the Roshi said I could go swimming while he and his friends sat on the beach. It was the first time I was swimming in a year and it was wonderful. Looking back at the shore it was strange to see the Roshi in his robes sitting on the beach.

We took the train back to Kyoto but had to switch trains about half way. When the Roshi was exiting the train one of his wooden geta got caught on the edge and fell through the space between the train and the platform. When the train pulled out I jumped on the tracks to retrieve his shoe. I was used to the NYC subway system where after a train left the station another one wasn’t along for a few minutes. I didn’t realize that Japan railways were so efficient that trains came in every minute. When I got on the tracks I heard screaming from the platform and I looked up to see a train barreling down on me. Fortunately I didn’t weigh too much for two men to grab each of my arms and lift me to safety, just before the train arrived.

When we got our train to Kyoto, again I sat across from the Roshi and again we were quiet. I looked at his face and he seemed to express a mixture of embarrassment at his mistake and appreciation of my (dumb) dedication.

10. Farewell Meal

For many generations the Nakaoji family were the groundskeepers for Shokoku-ji and its sister temples. Usually it was Nakaoji-san and Nakaoji san no okusan (Mrs) but occasionally even the grandfather still helped out. Whenever they came to the sodo they were treated with respect and affection by the monks. During my year there they were my biggest supporters, always encouraging me to make my best effort during sesshins, saying Gambatte kudasai.

On the day before I was to return to the US they invited me and a few of the monks to a goodbye feast at their house. We sat around on a hot August day eating bowl after bowl of vegetable sukiyaki and reminiscing about the year. I was experiencing a range of emotions. Tremendous love and appreciation for the monks and the Nakaojis, but also anxiety about going home. A few days before, my girlfriend from Cornell, Angel, had left me a message at Chotoku-in. When I returned her call she told me that my mom had told a few of my Cornell friends that my draft notice arrived and I was to report to active duty a week after I got home from Japan. She also filled me in on how the Vietnam war had heated up. So I was having thoughts about the transition from monk to soldier.

As the meal was coming to an end Ken san pulled me aside. Most of the monks in the sodo were on the severe side. Ken san was different, always upbeat and smiling. Even during intense meditation periods he was serene. He said to me, “So man san did you learn anything about Zen this year?” I guess I learned enough not to answer that type of question directly and I said, “Not about Zen, but I learned some things about myself.” Ken san said, “ Good answer.”

The next day I took a train to Tokyo, a plane to New York and my dad picked me up to take me back to Brooklyn. During the next 3 days the transition from sodo food to Zelda’s cooking took a toll on my stomach. Actually it is fair to say that my mom’s cooking saved me from going to Vietnam. But that’s a whole other story.

All of us in front of the sodo entrance: top row left to right:

Nakaoji san, monk, man san, Roshi, monk, jikijitsu san

Bottom row left to right: Gan san, Nakaoji san no okusan( Mrs), ken san, moku san)

Nakaoji-san and Man-san at farewell party

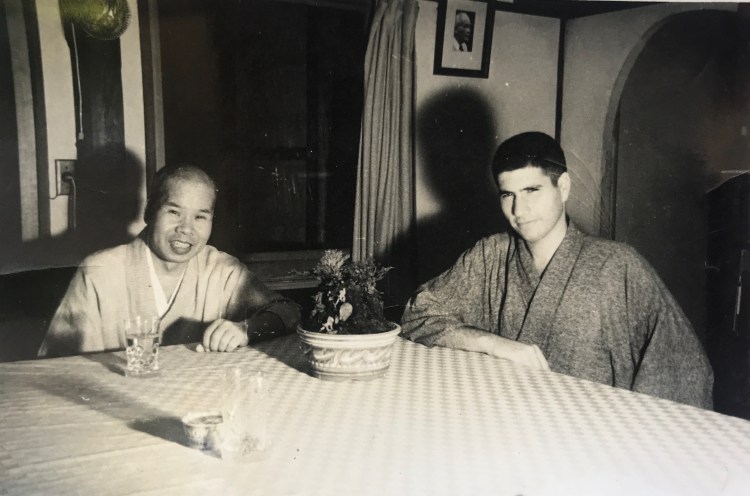

Ogata-san Man-san at Chotoku-in

Nakaojis on a lunch break