Herman Hesse’s Siddhartha is one of my favorite books, and I re-read it every few years. You probably don’t want to be around when I do because at several points in the book I sob loudly. Like the actual Buddha, Siddhartha leaves a privileged life to join a group of wandering ascetics, the samanas.

But while Buddha lived a simple life to his end days, Siddhartha’s journey included leveraging things he learned from the ascetics to become a wealthy merchant. My life took a similar turn (and did I mention that Siddhartha got into heavy gambling and was estranged from his son?).

As I’ve written in previous stories, I spent 1964-1965 doing Zen training at Shokoku-ji in Kyoto Japan. On a surface level the conditions in the monastery, especially for the youngest monk, don’t appear to be designed for happiness.

-Lack of mental stimulation, amusement- no TV, radio, music, phone, newspapers, books, or intimacy/sex;

-Lack of comfort- no beds, toilets, hot water, showers, heat in the winter or fans in the summer, and minimal amounts of food (I lost 1/4 of my body weight);

-Pain- many hours of sitting in the lotus position, in pain, without moving.

Yet the Dalai Lama has stated that Buddhism is a religion of happiness, and amazingly, that year was probably the happiest and healthiest in my life. There were several aspects of monastery life that do consistently lead to higher levels of happiness. 50 years after I left Zen training, neuroscience has confirmed the positive impact of these practices on brain health and functioning.

-Mindfulness- my life was simple manual labor (sweeping, cleaning, weeding), repetitive chanting, meditating, and maintaining silence during most of the day. This allowed me to practice mindful attention and focus on the activity at hand.

-Gratitude- we practiced gratitude throughout the day, before we ate even one grain of rice, before we went into the bathhouse, before we went to see the Zen master.

-Zazen/Meditation- deep levels of tranquility not only provide a peaceful, clear mind, the sensations in my body were also extremely pleasurable. As Walt Whitman exclaimed, “ I sing the body electric.” The buzzing and streaming in my body felt so good that I all I needed to be happy was to sit there and be alive.

When I left the monastery in August 1965 there was knowledge embedded in me. This wisdom was nothing I learned through reading, or discussion, or even reflection. It was just there in an unshakeable way, already proven forever in my being.

Three Lessons

1. I needed very little, in terms of money or possessions, to be happy. I had many of the sources of happiness within me. Siddhartha comforted himself with the knowledge, “I can think, I can wait , I can fast.” For me it was, “I can control my attention, my body and my breath.”

2. I realized that if I kept my monthly “nut” (living expenses) low I could have many degrees of freedom in life. I could learn what I wanted to learn, take risks, have experiences, and “follow my bliss.” I wouldn’t have to do work I didn’t want to do or work for someone I didn’t respect.

3. If I ever did acquire money it would be easy to be generous because I didn’t need that much for myself.

When I left the monastery to join the US Army I had no inkling that 6 years later these lessons were going to put me on a path to earning big fees as an executive coach for multinational companies, and to follow John Wesley’s famous advice, “Make all you can, save all you can, give all you can.”

Over the course of my life I would say principles 2 and 3 held up very well, and proved to be real for me. Learning #1 not so much. The practices are effective but at 21, I underestimated the impact of romantic relationships, family conflict, the Importance of friends and how much therapy I would need.

From 1965-1971 I had two major commitments and they both lasted 6 years. I was in the Army from September 5, 1965 to September 5, 1971, with active duty at Ft. Gordon in Augusta, Georgia, and Ft. Sill in Lawton, Oklahoma. My national guard/reserve duty was in an infantry unit in Harlem, and a civil affairs unit in Norristown, Pennsylvania. At the same time, I pursued a masters and Ph. D. in Clinical Psychology at Temple University in Philadelphia and did my internship at Norristown State Hospital.

As I looked to both of these commitments ending in September 1971, when I was 27, I thought “when am I ever going to have this kind of freedom, with no responsibilities”? I made two decisions, both possible because I knew I could live on small amounts of money. One, I had saved $2,000 from my paid internship and I embarked on a 9 month trip around the world. The entire trip, including airfare, cost $1,500. Two, I took a job, starting in San Diego in June 1972, with the National Center for the Exploration of Human Potential. Even with my Ph. D. all they could pay me was $400/month. But I was fascinated by their approach and I knew I could live on that salary, so I said Yes. Of course, I didn’t know it at the time but both of these decisions led to experiences that not only equipped me to be an international executive coach, but for many years gave me a competitive advantage over other coaches in the US.

Traveling the World

My trip started in St. Malo, France on the Brittany coast; then on to Paris, Velez Malaga on the Costa Del Sol, Essaouira Morocco, and Kyoto Japan. What kept the cost of the trip so low? In those days you could fly Icelandic Airlines to Europe and also get on charter flights with Christian missionaries to Asia. I bought a car in St. Malo, drove it around Europe and sold it for the same amount back in Paris. In Japan, I lived in the monastery for $10/month and I actually left Morocco with more money than I had when I entered.

All the places were wonderful but I’ll only describe the experience in Essaouira. It is situated on an exquisite 1.5-mile crescent beach, often traversed by camels carrying large stones. At the end of the beach is an ancient shipyard, still active, and a walled city. Inside town I would get mounds of vegetable couscous, mint tea with the leaves and sprigs, and freshly made yogurt in a glass, all for $1. At midnight there was an expat poker game. Most of the time I was the only American, and often it seemed like I was the only one who knew how to play poker. I was definitely the only one who didn’t smoke hashish. So you see how I came to leave Morocco with extra francs, pounds and Deutschmarks.

How did this trip help me in my eventual career? The places I stayed and the people I met gave me an education about culture, perceptions, stereotypes, etc. Based on the saying “You never really understand your culture until you leave,” it also helped me understand the U.S. better. When I eventually became a coach in 1986, this cultural knowledge made me very valuable to PepsiCo International.

The National Center for Exploration of Human Potential (NCEHP)

As I was finishing up my time at Norristown State Hospital I realized that my life consisted of focusing on the negative aspects of human behavior. At the time Abraham Maslow was encouraging psychologists to study self-actualized people and he, among others, started “the third wave” of psychology, the Human Potential Movement.

A lot of the activity was in San Diego and I took 3 weeks off from my internship to experience “positive” psychology at the NCEHP. I loved them and they loved me and they offered me a job. I asked if I could start in 9 months after my trip and they agreed. So I left my second stay at the monastery and arrived for work at the center in June 1972.

While Maslow studied self-actualized people, Herb Otto, the founder of NCEHP, had developed methods for the average person to identify their strengths and develop their potential. In groups of 12, one by one participants would open up about their lives, aspirations, and peak experiences. The group would focus on individuals and make them aware of their gifts, talents, values, intentions, and give them a picture of what they could be like if they leveraged all of their strengths.

The participants in the 3-week program were teachers, ministers, nurses, psychologists, social workers, etc. who wanted to experience these methods, but also learn to go back home and teach them in their communities. So we also had Train the Trainer sessions where they had the experience of facilitating these kinds of groups. We ran three, three-week programs a summer, training about 100 leaders. There were many other growth activities like Reiki, Rolfing, massage, free form dance, yoga, visits from gurus like Fritz Perls, and occasional nudism. Overall a very joyous time.

One vivid memory for me was when my yoga teacher Jim invited me to the nudist colony where he lived, in a canyon outside of San Diego. He wanted me to be his partner in the doubles tennis tournament. So we went out there, in front of the crowd, with only our rackets, socks and tennis shoes. We were doing fairly well when Jim rushed the net and took a shot in the “family jewels.” Even Jim’s 20 years of yoga training couldn’t overcome that blow and we had to forfeit the match.

I worked at the executive director of the NCEHP from 1972 to 1975, and at the time had no interest or intention of ever getting into the business world. However, I was acquiring very marketable skills. The ability to spot people’s strengths very quickly and get them to believe in their potential gave me a great foundation as a coach. The facilitating skills to teach skills, and motivate behavior change in a seminar setting was very valuable. In addition I trained over 400 trainers, which was the skill that eventually got me in the door of corporate training and coaching.

In my last year at the Center I met my future wife and we moved to Ohio. Still in my “ Thoreau at Walden Pond” approach to life, we found a small farmhouse on 13 acres in Wayne National Forest, 5 miles outside of Athens. My real estate taxes were $88/year and my mortgage was $75/month, and between doing some training for people I had met at the Center and flea marketing, I made about $6,000 a year.

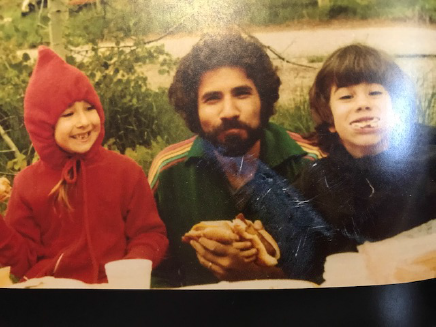

My daughter Allison was born in July 1976, and then in 1977 my wife got pregnant with my son Joshua. Even with the second kid on the way I was still following Thoreau’s advice, “Simplify, Simplify, Simplify,” and “Beware of ventures that require new clothes.” Most of the time I was in my overalls, and that was what I was wearing one day when I got a call from Bob Bolton. Bob and Dot Bolton had been in my groups at NCEHP, and had started their own center, The Ridge, in Cazenovia, NY. I worked for them on occasion over the years. Bob called me to tell me that he had made the switch from training teachers to corporate training for Wilson Learning. He told me that he had convinced the CEO Larry Wilson that I was an expert in training trainers and that Larry should hire me to train the Wilson Learning team. I was only half listening because I knew nothing about business and had no interest in it. And then Bob said, “ Larry will pay you $500/day.”

So that was the turning point. I looked at my wife, who was about to give birth to our second child, and I said to myself maybe it’s time to let go of Thoreau and make more than $6k a year as a father of two kids.

I worked for Larry Wilson and Bob and Dot for 3 years, mostly part time, and then in 1980 I accepted my first full time job, as head of HR for a resort real estate company on Hilton Head Island, South Carolina. This was the first time that I was making enough money for the “giving” part of my principles to kick in. If anything, having children reinforced this desire. I remember holding my daughter when she was a baby and feeling the anguish of what it would be like to not have enough to feed her.

On Hilton Head I received a decent salary, and doubled that by playing in a high stakes poker game on HH and Savannah, GA. The game was composed of wealthy real estate developers, guys who owned chains of BBQ restaurants, etc. When I was 12 years old I read a book by Herbert Yardley called, “ The Education of a Poker Player.” It instilled in me a lifelong dream to see if I could make a living by my wits, playing poker.

So those years were kind of like a dream for me. We lived on my salary, and like Robin Hood I took from the rich and used all my poker money for some wonderful projects. One was with Save the Children, supporting the Edisto tribe, and another was partnering with Rev. Williams from the Baptist Church. This church was the oldest one on Hilton Head, founded by descendants of slaves who had escaped to Hilton Head and Daufuskie Islands. We rented a huge warehouse and filled it with people donating their excess goods, sporting equipment, and clothes. Things were sold for low prices and it was almost all profit which went to the Edisto tribe and the church. On Sundays I would go to Rev. Williams services. The sounds, spirit, and sermon put me on another plane. In addition to that was a hug from Rev. Williams after the service. He was a big guy, about the size of my father, but taller. Probably the best “ comforter” I ever met. When Rev. Williams hugged you, you felt all was right with the world. So that is where John Wesley’s advice “ Make all you can, save all you can, give all you can” first became real for me. I was taking big risks every week playing at very high stakes, being successful, and converting that to do good in the world.

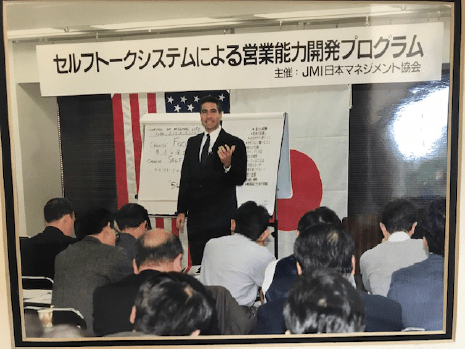

1986 is when everything came together and again Bob and Dot Bolton played the key role. Dot had just secured Pepsi Cola International as a client for Ridge and she sent me on my first coaching assignment for John Fulkerson and John Pearl. This is where all my learning, experiences, and travel combined to help me get off to a good start as an executive coach.

John introduced me to his wife Hilary, who worked for Mike Peel and Mike Feiner on the domestic side of the business.

So it’s been a great 34-year ride as a coach, working with thousands of executives. About 15 years ago, John Futterknecht, Ben Sorensen, and I started a coaching/training company and we dedicated ourselves to teaching skills that help people in their careers, self-care, and relationships.

Reflecting on my life, I certainly can take no credit for foresight or planning. I never thought I would do anything in the business world, but being free of most money constraints when I was young allowed me to learn some valuable things and have important experiences. My friend John Pearl calls me a minimalist, which is mostly true. In the monastery my possessions consisted of a bowl, chopsticks, a robe, work clothes and a tanbuton mat that I folded up to sit on for zazen and unfolded and slept on at night. I enjoyed the simplicity and knowing that I could carry all of my possessions.

When COVID hit I moved to Los Alamos, New Mexico and lived in a small hotel room on the edge of town, only shopping for food. Living there I could feel the rhythms and routines of the monastery returning, and I enjoyed my time there.

As we used to say about Brooklyn, “You can take the boy out of the monastery, but you can’t take the monastery out of the boy.”

Great story of your development .

I learned a lot I didn’t know before re the details of how you lived.

You are a very talented, and fortunate man.

Knowing a little bit about your family in Brooklyn I wonder where you got your core values . Wherever it was , I’m glad you did and thanks for sharing.

LikeLike